Before 1796

1796 -1799

1800 - 1819

1820s

Late 19th Century

Litton Mill

Land Ownership

Slack & Mill

Connections

Living Conditions

Robert Blincoe

Censuses 1841 - 1891

"Meanwhile, as soon as Blincoe

found himself outside the hated walls, he set of again up Slack, a very

steep hill close to the mill, and made the best of his way to Litton ..."

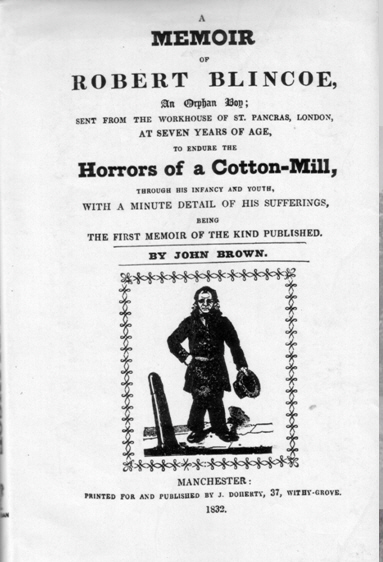

Much has been written about the cruelty and poor working conditions at Litton Mill in particular with reference to apprentice deaths. Much of the evidence against Litton Mill stems from the book "A Memoir of Robert Blincoe". The book contains great detail of the punishment and suffering Blincoe, and others, experienced whilst at Litton Mill. For example ...

"Palfrey, the Smith, had the task of

riveting irons upon any of the apprentices, whom the masters ordered,

and those were much like the irons usually put upon felons. Even young

women, if suspected of intending to run away, had irons riveted on

their ankles, and reaching by long links and rings up to the hips, and

in these they were compelled to walk to and from the mill to work and

to sleep. Blincoe asserts, he has known many girls served in this

manner. A handsome-looking girl, about the age of twenty years, who

came from the neighbourhood of Cromford, whose name was Phebe Rag,

being driven to desperation by ill-treatment, took the opportunity, one

dinner-time, when she was alone, and when she sup-posed no one saw her,

to take off her shoes and throw herself into the dam, at the end of the

bridge, next the apprentice house. Someone passing along, and seeing: a

pair of shoes, stopped. The poor girl had sunk once, and just as she

rose above the water he seized her by the hair. Blincoe thinks it was

Thomas Fox, the governor, who succeeded Milner, who rescued her. She

was nearly gone, and it was with some difficulty her life was saved.

When Mr. Needham heard of this, and being afraid the example might be

contagious, he ordered James Durant [Note Durant was shown living

Littonslack in 1811 and 1813], a journeyman-spinner who had been

apprenticed there, to take her away to her relations at Cromford, and

thus she escaped."

The book may be truthful, but it has also received criticism as being written primarily for the campaign for factory legislation.

Unsurprisingly Littonslack has connections with this suffering. James Durant (see above) lived at Littonslack. He had 2 children Mary and Margaret, born in 1811 and 1813 respectively. Robert Woodward (an overlooker at the mill) lived at Littonslack. He had 2 children whilst living there, Robert and Mary in 1804 and 1807 respectively. Robert Woodward was one of the villains cited many times in the Blincoe Memoir ...

"Robert Woodward once kicked and beat

Robert Blincoe, till his body was covered with wheals and bruises.

Being tired, or desirous of affording his young master the luxury of

amusing himself on the same subject, he took Blincoe to the

counting-house, and accused him  of wilfully spoiling his work. Without

waiting to hear what Blincoe, might to have to urge in his defence,

young Needham eagerly looked about for a stick; not finding one at

hand, he sent Woodward to an adjacent coppice called the Twitchell, to

cut a supply, and laughingly made Blincoe strip naked, and prepare

himself for a good flanking."

of wilfully spoiling his work. Without

waiting to hear what Blincoe, might to have to urge in his defence,

young Needham eagerly looked about for a stick; not finding one at

hand, he sent Woodward to an adjacent coppice called the Twitchell, to

cut a supply, and laughingly made Blincoe strip naked, and prepare

himself for a good flanking."

of wilfully spoiling his work. Without

waiting to hear what Blincoe, might to have to urge in his defence,

young Needham eagerly looked about for a stick; not finding one at

hand, he sent Woodward to an adjacent coppice called the Twitchell, to

cut a supply, and laughingly made Blincoe strip naked, and prepare

himself for a good flanking."

of wilfully spoiling his work. Without

waiting to hear what Blincoe, might to have to urge in his defence,

young Needham eagerly looked about for a stick; not finding one at

hand, he sent Woodward to an adjacent coppice called the Twitchell, to

cut a supply, and laughingly made Blincoe strip naked, and prepare

himself for a good flanking."Also William Mace, who lived at Littonslack, was buried in 1811. Normally the register show basic information. However on this occasion the registrar added a small comment . The entry read "William Mace of Litton Mill Slack; killed yesterday at Litton Cotton Mill".

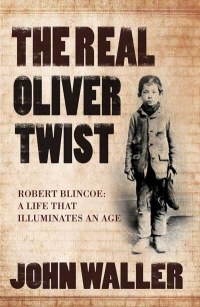

The Memoir of Robert Blincoe is still available from secondhand bookshops (as it was reprinted in 1977). Much of the book is available to read online via Google Books in Factory Lives. Also available is The Real Oliver Twist which reprints much of the book and argues that the Memoir was Dickens' basis for The Adventures of Oliver Twist.

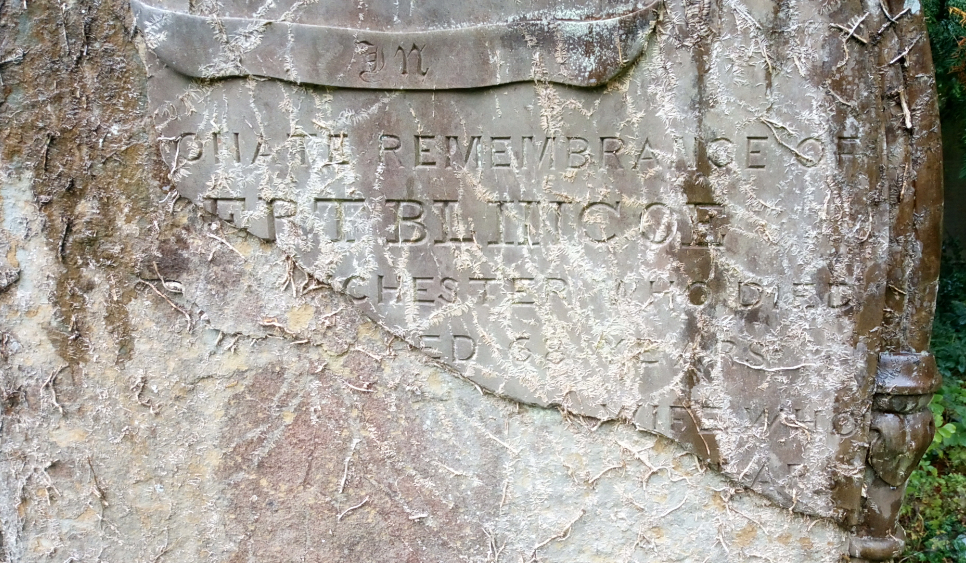

Robert Blincoe died in December 1860. His grave, and what remains of his gravestone is at St Christopher's Church, Pott Shrigley, Cheshire. The inscription reads [AFFECTI]ONATE REMEMBRANCE OF ROBERT BLINCOE [...] MANCHESTER AGED 68. His wife and other members of the family are buried there. Click on the pictures below for higher resolution versions.

December 2011 saw 2 books published about Robert Blincoe. The first is a novel "Blincoe's Progress", the second a factual book, "Robert Blincoe and the Cotton Trade."

Blincoe's Progress by Stuart Courtman

Parson Brown is the newly appointed local rector of Tideswell in Derbyshire. He is involved in a shady deal with the London workhouse wardens, resulting in children, including Blincoe, being moved into his parish. Blincoe is apprenticed to Ellis Needham, a friend of Brown’s and the owner of nearby Litton cotton mill.

Due to their immaturity, both Brown and Blincoe make mistakes, and they struggle with the consequences. Eventually, they each fall in love with local girls. But can they have the ones they love, or will the repercussions of their mistakes prevent them realising their dreams?

This is the story of the harsh life surrounding the cotton industry; a life that proves to be difficult and complicated for apprentices, workers, mill owners, and even the local parson.

Stuart moved to the Peak District in 2002 to live in a hamlet established in the eighteenth century industrial revolution. In 1865, the hamlet was described as “a small row of cottages, standing on a bleak and wild looking moor-like prominence, as if the buildings had been lifted out of the adjoining valley to look about them.” That valley is dominated by Litton and Cressbrook cotton mills and Stuart was drawn into the fascinating history of the area. The research threw up many interesting facts but also left unanswered questions.

Stuart’s first novel Blincoe’s Progress fills those gaps with a fiction set in the eighteenth century centred around local characters, including: Molly Baker, Landlady of the Red Lion at Litton; Ellis Needham, owner of Litton cotton mill; William Newton, manager of Cressbrook mill, Parson Brown and his maid, who live in the vicarage at Tideswell, Woodward, the brutal overlooker from Litton mill, and many ill-treated apprentices and mill workers.

Robert Blincoe and the Cotton Trade by Stuart Courtman

‘A Memoir of Robert Blincoe’ published in 1828 was

influential in improving the working conditions of children in

factories. It is also believed that Charles Dickens based his character

Oliver Twist on Robert Blincoe. This book contains the original full

1828 text of the memoir and historical notes by Stuart Courtman.

‘A Memoir of Robert Blincoe’ published in 1828 was

influential in improving the working conditions of children in

factories. It is also believed that Charles Dickens based his character

Oliver Twist on Robert Blincoe. This book contains the original full

1828 text of the memoir and historical notes by Stuart Courtman.The historical notes explore the influences that led to the development of mechanised cotton production and discuss the political and economic changes that shaped the industry. There is examination of the treatment of children in workhouses and mills, and discussion of how the relative conditions at Litton and Cressbrook mills have been perceived over the centuries. There are notes on the wider global forces that contributed to the anti-slavery movements and the demise of cotton manufacturing in India. There are chapters which account for the historical agency of individuals such as Ellis Needham, owner of Litton mill, William Newton, manager of nearby Cressbrook mill and Parson Brown, the local Tideswell vicar.

The text of the memoir has been reproduced, unchanged from the 1828 publication. Spellings are retained with some archaic spelling of words, possibly some misspellings and many inconsistencies of spelling. Similarly the punctuation has been reproduced from this version; again with its oddities. No attempt has been made to modernise the words or language.

It is hoped that the notes here will enhance the reading of both the 1828 memoir, and the novel, Blincoe’s Progress.